The Gospel Writers

Moderator: Moderators

-

Realworldjack

- Guru

- Posts: 2397

- Joined: Thu Oct 10, 2013 12:52 pm

- Location: real world

- Has thanked: 3 times

- Been thanked: 50 times

The Gospel Writers

Post #1What can we know (demonstrate) about the authors of what we call "The Gospels"? Notice carefully that I am not talking about opinions here, but rather what we can know to be a fact, and how we would go about demonstrating it to be a fact we can know?

- Difflugia

- Prodigy

- Posts: 3035

- Joined: Wed Jun 12, 2019 10:25 am

- Location: Michigan

- Has thanked: 3267 times

- Been thanked: 2017 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #61Not at all. I readily acknowledge that my debate opponents "may very well" have reasonable justifications for believing what they do (broad sense). That doesn't mean that any given opponent necessarily does, however (narrow sense).Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amMy friend, it is either true, or it is false. It seems to me you may be avoiding the question?

The two aren't exclusive. You really ought to be using the facts and evidence we have to decide what is probably correct.Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amThe point here is, I do not make decisions based upon what I believe may "probably" be correct, but rather upon the facts, and evidence we have.

Yes.Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amWhen we are talking about the resurrection of Jesus, the "probability" of a resurrection is not very good at all, to which we can all agree.

The low probability assigned to the resurrection is because of the facts and evidence, not despite them.Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amHowever, the "probability" of Jesus being resurrected, can do nothing whatsoever to getting us closer to the truth. Only the facts, and evidence can do this.

You keep asserting variations of this, but saying that you base conclusions on the facts instead of the probabilities is like claiming to understand English based on the nouns instead of the verbs.Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amSo then, you seem to believe your decisions to be sound because they are built upon the "probabilities", while I tend to base my conclusions upon the facts, and evidence we have, ignoring the "probabilities", because I happen to understand that the "probabilities" have nothing to do with what the truth would actually be.

Believe it or not, you're starting to convince me.Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amIt is my hope that my explanation above has eliminated your suspicion, because I can assure you when I am making such a major life decision, I am not in any way considering the "probabilities", but am rather only considering the facts, and evidence involved.

No. The facts and evidence alone often have many "very possible" explanations. Assigning probabilities, even informally, can help narrow down which ideas to seriously consider. Here's a hypothetical set of facts:Realworldjack wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:07 amSo then, are you suggesting that the "probabilities produce" better decisions than the then facts, and evidence, involved?

- I am not hungry.

- I remember making a sandwich.

- I remember eating the sandwich.

- There are bread crumbs on the counter where I remember making the sandwich.

-

Realworldjack

- Guru

- Posts: 2397

- Joined: Thu Oct 10, 2013 12:52 pm

- Location: real world

- Has thanked: 3 times

- Been thanked: 50 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #62[Replying to Difflugia in post #61]

No! You are way off here. If the probability of wives remaining faithful to their husbands is very low, should I make a decision to divorce my wife based upon the probabilities? Or, should I only look at the facts, and evidence involved? We could continue on with many other examples. As I have said, if we only look at the probabilities of a resurrection occurring then we would all have to conclude that a resurrection never happened. I have no problem with those who make decisions in this way. The problem comes in when these same folks want to insist that I have no reason for the position I hold.

Allow me to say it like I have many times in the past. There are many, many folks on both sides of the equation as far as Christianity is concerned, who are under the impression that it is all so simple. However, those who have actually done the work know very well that it is not that simple at all, and there are no easy answers.

Well allow us to apply this to the topic at hand. You seem to believe the author of Luke, and Acts, was using a literary device, and did not intend to be understood as being present to witness the events he records. I understand your argument very well. However, even though you believe you have reason to hold this position, there is very good reason for those to hold the position that the use of the words, "we", and "us" would indeed indicate that the author was present to witness the events recorded. What I am saying is, it would be intellectually dishonest to claim there would be no reason for one to hold such a position.Not at all. I readily acknowledge that my debate opponents "may very well" have reasonable justifications for believing what they do (broad sense). That doesn't mean that any given opponent necessarily does, however (narrow sense).

I truly do not understand this sort of thinking? Even if I were to weigh the facts, and evidence, and come up with in my mind what would probably be correct, how would this get me any closer to the truth? If you were on trial for a crime, and your life was on the line, would you want the jury to attempt to decide what they think probably happened in order to convict you? Or, would you rather them be "convinced beyond any reasonable doubt"?The two aren't exclusive. You really ought to be using the facts and evidence we have to decide what is probably correct.

Again, there seem to be those who have trouble separating fact, from opinion. The idea that the facts, and evidence contributes to the low possibility of the resurrection is an opinion, not a fact, and not everyone would agree with your opinion. The actual reason the resurrection would not be probable is because it would be beyond human explanation, and understanding, and it is not an everyday occurrence. The authors of the NT lying about the resurrection is the more probable answer because folks lie everyday. So, how does this get us any closer to knowing if the authors were lying, as opposed to reporting fact? It does not. This is why one should leave the probabilities out of the equation, and move on to the facts, and evidence involved.The low probability assigned to the resurrection is because of the facts and evidence, not despite them.

You keep asserting variations of this, but saying that you base conclusions on the facts instead of the probabilities is like claiming to understand English based on the nouns instead of the verbs.

No! You are way off here. If the probability of wives remaining faithful to their husbands is very low, should I make a decision to divorce my wife based upon the probabilities? Or, should I only look at the facts, and evidence involved? We could continue on with many other examples. As I have said, if we only look at the probabilities of a resurrection occurring then we would all have to conclude that a resurrection never happened. I have no problem with those who make decisions in this way. The problem comes in when these same folks want to insist that I have no reason for the position I hold.

I am afraid not. Because you see, when you begin to assign probabilities, you very well could eliminate the correct answer simply upon the probabilities you have assigned to them.No. The facts and evidence alone often have many "very possible" explanations. Assigning probabilities, even informally, can help narrow down which ideas to seriously consider.

I think you would have to agree this analogy is ridiculous, and we would do far better to stick to a "real world" example like the resurrection we have already mentioned. Again, if we simply consider the probabilities, we would all have to conclude that a resurrection did not occur. However, when one moves beyond the probabilities to actually examine the real facts, and evidence, they will certainly see that there is far more to this thing, than simply the probabilities. They will also have to clearly concede that considering the probabilities of a resurrection gets us nowhere closer to what the truth would be in this case.I am not hungry.

I remember making a sandwich.

I remember eating the sandwich.

There are bread crumbs on the counter where I remember making the sandwich.

"I made and ate a sandwich" has exactly the same amount of explanatory power as "aliens beamed food into my stomach and bread crumbs onto the counter, then implanted a series of false memories in my head." The facts and evidence are consistent with and support both of these scenarios. Considering the relative probabilities of the two explanations, I would like to think that neither of us would wonder which of the explanations to take seriously.

Allow me to say it like I have many times in the past. There are many, many folks on both sides of the equation as far as Christianity is concerned, who are under the impression that it is all so simple. However, those who have actually done the work know very well that it is not that simple at all, and there are no easy answers.

- Goose

- Guru

- Posts: 1707

- Joined: Wed Oct 02, 2013 6:49 pm

- Location: The Great White North

- Has thanked: 79 times

- Been thanked: 68 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #63You are talking about assigning prior probabilities to various hypothesis (or explanations). But we don’t eliminate a particular hypothesis simply based on low prior probability. Nor do we make our decisions based on prior probabilities if we are making our decisions based on probabilities. We prefer one hypothesis over the other because of posterior probability given the evidence. So we can informally say the hypothesis that “I made and ate a sandwich” has a much higher prior probability than the “aliens” hypothesis. But that only speaks of prior belief in the hypothesis before considering the given evidence.Difflugia wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 10:09 amNo. The facts and evidence alone often have many "very possible" explanations. Assigning probabilities, even informally, can help narrow down which ideas to seriously consider. Here's a hypothetical set of facts:"I made and ate a sandwich" has exactly the same amount of explanatory power as "aliens beamed food into my stomach and bread crumbs onto the counter, then implanted a series of false memories in my head." The facts and evidence are consistent with and support both of these scenarios. Considering the relative probabilities of the two explanations, I would like to think that neither of us would wonder which of the explanations to take seriously.

- I am not hungry.

- I remember making a sandwich.

- I remember eating the sandwich.

- There are bread crumbs on the counter where I remember making the sandwich.

However, let’s introduce one further piece of evidence to your set of facts.

I am Steven Hawking

Now, let’s consider the posterior probability that you “made and ate a sandwich” (assuming you mean you made the sandwich yourself with your own hands) given the fact you are Steven Hawking.

We can apply Bayes Theorem.

Let A = I made and ate sandwich

Let B = I am Steven Hawking

P(A) = let’s say 90% since we believe most people have made and ate a sandwich

P(B|A) = 0% (since you cannot be Steven Hawking if you made and ate a sandwich)

P(B|~A) = 100% (since you are Steven Hawking)

P(~A) = 10%

P(A|B) = P(B|A)P(A) / P(B|A)P(A) + P(B|~A)P(~A) = 0 x .9 / 0 x .9 + 1 x .1 = 0/.1 = 0

Thus the probability you made and ate a sandwich given that you are Steven Hawking is 0, or impossible.

In light of this evidence the “alien” hypothesis, although it has a very low prior probability, still has a non-zero posterior probability thereby giving it a higher probability than the “I made and ate a sandwich” hypothesis. Given this evidence and given these are the only two hypotheses under consideration you must provisionally accept the “alien” hypothesis if you are basing your beliefs on probabilities.

Now that we have that out of the way go ahead and show us your argument that demonstrates your earlier claim.

Please show your work and underlying assumptions.

When you are finished I’m going to apply your argument(s) to other secular works to see what happens.

Things atheists say:

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

- Difflugia

- Prodigy

- Posts: 3035

- Joined: Wed Jun 12, 2019 10:25 am

- Location: Michigan

- Has thanked: 3267 times

- Been thanked: 2017 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #64If we posit that I really am Steven Hawking, then I only have one quibble with your analysis. The probability the Steven Hawking made the sandwich isn't literally zero. It's low enough that I'd say it rounds to zero and one would colloquially say that it's impossible, but if I had to guess about orders of "impossible," there's a better probability of Steven Hawking making the sandwich than aliens making it look like he did. For one thing, we actually know that Steven Hawking exists.Goose wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:39 pmYou are talking about assigning prior probabilities to various hypothesis (or explanations). But we don’t eliminate a particular hypothesis simply based on low prior probability. Nor do we make our decisions based on prior probabilities if we are making our decisions based on probabilities. We prefer one hypothesis over the other because of posterior probability given the evidence. So we can informally say the hypothesis that “I made and ate a sandwich” has a much higher prior probability than the “aliens” hypothesis. But that only speaks of prior belief in the hypothesis before considering the given evidence.

However, let’s introduce one further piece of evidence to your set of facts.

I am Steven Hawking

Now, let’s consider the posterior probability that you “made and ate a sandwich” (assuming you mean you made the sandwich yourself with your own hands) given the fact you are Steven Hawking.

We can apply Bayes Theorem.

Let A = I made and ate sandwich

Let B = I am Steven Hawking

P(A) = let’s say 90% since we believe most people have made and ate a sandwich

P(B|A) = 0% (false, since you cannot be Steven Hawking if made and ate a sandwich)

P(B|~A) = 100% (true, since you are Steven Hawking)

P(~A) = 10%

P(A|B) = P(B|A)P(A) / P(B|A)P(A) + P(B|~A)P(~A) = 0 x .9 / 0 x .9 + 1 x .1 = 0/.1 = 0Thus the probability you made and ate a sandwich given that you are Steven Hawking is 0, or impossible.

In light of this evidence the “alien” hypothesis, although it has a very low prior probability, still has a non-zero posterior probability thereby giving it a higher probability than the “I made and ate a sandwich” hypothesis. Given this evidence and given these are the only two hypotheses under consideration you must provisionally accept the “alien” hypothesis if you are basing your beliefs on probabilities.

Now that we have that out of the way go ahead and show us your argument that demonstrates your earlier claim

To use this as a teaching moment, though, none of the wrinkles in any of the biblical claims amount to "I am Steven Hawking," but rather. "Goose says that I'm Steven Hawking." The balance of probability is still that I made the sandwich, but with an added bit of explanation that Goose is simply wrong about me.

If that's all you're going to do, you don't need me to help you. If you want to continue a discussion in the vein of the earlier part of the thread about any of the Gospels, I'm game. I enjoy reading through the works of the Church Fathers, hypothesizing about their relationship with and dependence on each other, and discussing what that means for Christian tradition. If you feel that your argument depends on making a case that Irenaeus is as reliable as Herodotus, then I'll try to be fair about addressing it.

If you start asking me to defend a historical method in general again, though, then you can just have the last word. I'm willing to acknowledge that it's important, but I find it tedious and uninteresting.

- Goose

- Guru

- Posts: 1707

- Joined: Wed Oct 02, 2013 6:49 pm

- Location: The Great White North

- Has thanked: 79 times

- Been thanked: 68 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #65Wow, okay. I didn’t expect you to go that way. It would take nothing short of a miracle for Steven Hawking (a man with, so far, incurable and advanced ALS) to get up out of his chair, walk into the kitchen, and make himself a PB&J on whole wheat. I mean we are talking about the spontaneous regeneration of millions of neurons here. You concede it’s probability is so low it’s "impossible." On what grounds do you argue it’s a non-zero probability though? Of the millions of times Hawking tried to get up did he ever even get up once? Yet, you argue that explanation is more probable than the naturalistic explanation that aliens implanted the belief.Difflugia wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 2:38 pmIf we posit that I really am Steven Hawking, then I only have one quibble with your analysis. The probability the Steven Hawking made the sandwich isn't literally zero. It's low enough that I'd say it rounds to zero and one would colloquially say that it's impossible, but if I had to guess about orders of "impossible," there's a better probability of Steven Hawking making the sandwich than aliens making it look like he did. For one thing, we actually know that Steven Hawking exists.Goose wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 1:39 pmYou are talking about assigning prior probabilities to various hypothesis (or explanations). But we don’t eliminate a particular hypothesis simply based on low prior probability. Nor do we make our decisions based on prior probabilities if we are making our decisions based on probabilities. We prefer one hypothesis over the other because of posterior probability given the evidence. So we can informally say the hypothesis that “I made and ate a sandwich” has a much higher prior probability than the “aliens” hypothesis. But that only speaks of prior belief in the hypothesis before considering the given evidence.

However, let’s introduce one further piece of evidence to your set of facts.

I am Steven Hawking

Now, let’s consider the posterior probability that you “made and ate a sandwich” (assuming you mean you made the sandwich yourself with your own hands) given the fact you are Steven Hawking.

We can apply Bayes Theorem.

Let A = I made and ate sandwich

Let B = I am Steven Hawking

P(A) = let’s say 90% since we believe most people have made and ate a sandwich

P(B|A) = 0% (false, since you cannot be Steven Hawking if made and ate a sandwich)

P(B|~A) = 100% (true, since you are Steven Hawking)

P(~A) = 10%

P(A|B) = P(B|A)P(A) / P(B|A)P(A) + P(B|~A)P(~A) = 0 x .9 / 0 x .9 + 1 x .1 = 0/.1 = 0Thus the probability you made and ate a sandwich given that you are Steven Hawking is 0, or impossible.

In light of this evidence the “alien” hypothesis, although it has a very low prior probability, still has a non-zero posterior probability thereby giving it a higher probability than the “I made and ate a sandwich” hypothesis. Given this evidence and given these are the only two hypotheses under consideration you must provisionally accept the “alien” hypothesis if you are basing your beliefs on probabilities.

Now that we have that out of the way go ahead and show us your argument that demonstrates your earlier claim

As for arguing there’s a better probability Steven Hawking made the sandwich because we know he exists. Well, firstly, we also know highly intelligent life exists in the universe too. And given the vastness of the universe it seems there’s at least a non-zero probability that highly intelligent life exists elsewhere. So it doesn’t seem the fact of Hawking’s existence increases the probability of him making the sandwich over aliens implanting the belief. Secondly, you are highlighting the arbitrary and subjective nature of these kinds of arguments. You are just arbitrarily assigning higher probabilities to certain propositions you prefer based upon nothing more than your personal intuition.

You’re using this moment to teach circularity then. Please stop. I can’t be wrong about you, remember it is one of several facts you (or whomever the example is supposed to be in the hypothetical example) is Steven Hawking. What you are suggesting here is that because one desires one’s preferred hypothesis to not be incorrect, it’s therefore the facts which must be incorrect, not the hypothesis.To use this as a teaching moment, though, none of the wrinkles in any of the biblical claims amount to "I am Steven Hawking," but rather. "Goose says that I'm Steven Hawking." The balance of probability is still that I made the sandwich, but with an added bit of explanation that Goose is simply wrong about me.

Yes, I want to continue a discussion about who wrote any of the Gospels. I choose the Gospel of John for a start. I want you to finally make your argument to support your claim that “it's probable that none of the Gospels was written by the person to whom it is traditionally ascribed.” And I want you to do that by arguing from probability since you seem to think such a probability argument can be made.If that's all you're going to do, you don't need me to help you. If you want to continue a discussion in the vein of the earlier part of the thread about any of the Gospels, I'm game. I enjoy reading through the works of the Church Fathers, hypothesizing about their relationship with and dependence on each other, and discussing what that means for Christian tradition. If you feel that your argument depends on making a case that Irenaeus is as reliable as Herodotus, then I'll try to be fair about addressing it.

This is the second time I’m asking. If you can't do it, just say so.

Let me see if I have this straight. It seems you want to debate an historical question like who wrote the Gospels in a vacuum without having your reasoning held to account by being shown how your historical methodology might have absurd affects on the rest of history because you find it tedious and uninteresting? That doesn’t sound like a sincere pursuit of history to me.If you start asking me to defend a historical method in general again, though, then you can just have the last word. I'm willing to acknowledge that it's important, but I find it tedious and uninteresting.

Things atheists say:

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

- Difflugia

- Prodigy

- Posts: 3035

- Joined: Wed Jun 12, 2019 10:25 am

- Location: Michigan

- Has thanked: 3267 times

- Been thanked: 2017 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #66That's adorable.

Either that or I find tedious your habit of preferring word games and definition wars to examining actual evidence. Take your pick.Goose wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 8:16 pmLet me see if I have this straight. It seems you want to debate an historical question like who wrote the Gospels in a vacuum without having your reasoning held to account by being shown how your historical methodology might have absurd affects on the rest of history because you find it tedious and uninteresting? That doesn’t sound like a sincere pursuit of history to me.

Modern, secular scholars are in agreement that John, son of Zebedee is unlikely the author of the Gospel of John. Most broadly agree (despite disagreeing with other conclusions) with Rudolf Bultmann (1950) and C. H. Dodd (1953) in seeing the result of a group process involving multiple sources, multiple redactions, or both from a "Johannine school" of Christians.

After the middle of the twentieth century, all commentators that I found arguing for the Apostle John as author (Craig Blomberg, Andreas Köstenberger, Charles Quarles, Craig Keener) are sectarian inerrantists that also argue that all of the traditional ascriptions for the other NT books are correct.

The evidence for the argument that John of Zebedee wrote the Gospel of John can be summed up with the following:

- The "Beloved Disciple" mentioned in the Gospel and taken to be its author might mean John of Zebedee.

- Irenaeus (Against Heresies, 3.1.2) claimed that the Fourth Gospel was written by "John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia."

Is the Beloved Disciple meant to be John, son of Zebedee? Since the author of the Gospel insists on avoiding the disciple's name whenever explicitly mentioned as "beloved," it makes sense to think that the author doesn't reference the disciple's name at all. It's worth noting, however, that John's Gospel only names five of the twelve (we presume twelve; the Gospel doesn't explicitly say that either) disciples in the first place: Peter, Andrew, Philip, Nathaniel, and Thomas. Based on the placement of the diners at the Last Supper, though, I think John is implied. As an aside, it seems funny to me in this context that while apologists are willing to stake the argument on the implication of John as the beloved disciple, they work overtime to deny the implication from the same Gospel that Jesus wasn't of Davidic descent (7:41-43).

Is the Beloved Disciple, whoever he is (the Greek uses masculine grammar), intended to be the author? That hinges on how one reads John 21:24:

While apologists universally assert that this is a claim of authorship, scholars are a bit more careful. Is this claiming that the Beloved Disciple is the author himself, that he was merely the author's source, or is it narrowly referencing the story in vv. 20-23? On pp. 246-247 of Rhetoric and Reference in the Fourth Gospel, Margaret Davies writes:This ["the disciple whom Jesus loved" from 21:20] is the disciple that bears witness of these things, and wrote these things. And we know that his witness is true.

On page 251, Davies concludes her chapter about the Gospel's authorship this way:The identification of the beloved disciple as the author of the Fourth Gospel rests on an interpretation of Jn 21.24. Immediately after an account of the resurrected Jesus' conversation with Peter about the fate of the beloved disciple, the text reads: 'This is the disciple who bears witness concerning these things and who wrote or who caused to be written [cf. 19.19, 22] these things, and we know that his witness is true'. It is not unnatural to interpret this as an attribution of the Gospel to the beloved disciple by the authors (we) of 21.24, although this may mean no more than that the Fourth Gospel is based on the witness and writings of the beloved disciple, not that our present Gospel was written by him, but it is more likely that the beloved disciple bore witness to Jesus' statement about his fate in 21.22. Certainly, 21.24 was not written by him. Moreover, the beloved disciple is never identified with John in the Fourth Gospel, and his function is that of an ideal, perhaps Gentile, disciple (see Chapter 14).

That the Gospel is itself claiming to be written by John of Zebedee depends on the interpretation of a verse that most scholars consider to be not only ambiguous, but an interpolation. The accuracy of the tradition that John of Zebedee is the author hinges on the judgement and trustworthiness of Irenaeus.The attribution of the Fourth Gospel to the apostle John is not found earlier than the second half of the second century. Irenaeus's claims were motivated by his opposition to heresies and are based on the obscure reference to the beloved disciple in Jn 21.24. The beloved disciple is pictured by the Fourth Gospel as close to Jesus, but is distinguished from Peter. The Synoptic Gospels give special prominence to Peter, James and John (e.g. Mt. 17.1; 26.37 and parallels), and Acts 12.2 tells of James's martyrdom. If all four Gospels are assumed to be describing the same historical characters straightforwardly and accurately, John is a likely candidate for identification with the beloved disciple as he is not otherwise mentioned in the Fourth Gospel. Jn 21.2 lists the sons of Zebedee and two other unnamed disciples amongst those present at the final resurrection appearance, and then goes on to mention the beloved disciple. Irenaeus must have assumed that the beloved disciple was a son of Zebedee, not one of the other unnamed disciples. The reference can, of course, be interpreted differently (see later, Chapter 14). Moreover, as Barrett notes (1978: 115), the paucity of references to the Fourth Gospel in the early period, outside of Gnostic circles, tells against any suggestion that it was published with apostolic authority.

Aside from the possible claim of the "Beloved Disciple" as the author, most other details of the Gospel argue against any of the original disciples being an author. It seems odd that the son of a Galilean fisherman in the first century would refer to the opponents of Jesus as "the Jews." John's Jesus is fond of ironic word play, some of which only works in Greek ("born again" vs. "born from above," for example). That would mean that the Galilean John of Zebedee is either remembering conversations with Jesus, his fellow Galilean, in Greek or incorporating later traditions into what is nominally a memoir, neither of which seems particularly likely.

- Goose

- Guru

- Posts: 1707

- Joined: Wed Oct 02, 2013 6:49 pm

- Location: The Great White North

- Has thanked: 79 times

- Been thanked: 68 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #67I’m not sure why you would think that’s adorable when it seems you failed to prove your claim which was...

After all the back and forth on probability, where did you demonstrate that probability in relation to John? If you did, I must have missed it. At least I know now why I had to ask twice.

Oh dear, it looks like I may have struck a nerve. But since you’ve not denied my assessment but rather made it a case of either X or Y and since (Y) is false (it’s false that I have a habit of preferring word games and definition wars to examining the evidence since I love examining evidence when given the chance) it logically follows I must conclude X (my assessment) is the case. Thank you for clearing that up.Either that or I find tedious your habit of preferring word games and definition wars to examining actual evidence. Take your pick.Goose wrote: ↑Thu Sep 17, 2020 8:16 pmLet me see if I have this straight. It seems you want to debate an historical question like who wrote the Gospels in a vacuum without having your reasoning held to account by being shown how your historical methodology might have absurd affects on the rest of history because you find it tedious and uninteresting? That doesn’t sound like a sincere pursuit of history to me.

By the way, historical methodology in regards to historical questions isn’t merely a word game or definitional war by the way. How can you properly examine the evidence without a proper historical method? Such a cavalier approach to historical methodology and how one's methodology might have absurd implications for the rest of history is indicative of one who isn’t really interested in treating Christian evidence fairly in my experience.

Not that’s it’s particularly relevant but Richard Bauckham seems to think the influence of Bultmann and form criticism is waning among scholarship and provides reasons as to why it ought to be abandoned. Bauckham, by the way, has argued the Gospels are based on eyewitness testimony. There are, however, scholars who have been employed by secular universities, though they are not secular scholars themselves, and argue for the traditional authorship of the Gospels such as F.F. Bruce, Craig Evans, and Timothy McGrew to name a few. But I would agree the majority of secular/critical scholars do not hold to traditional authorship if that is your point.Modern, secular scholars are in agreement that John, son of Zebedee is unlikely the author of the Gospel of John. Most broadly agree (despite disagreeing with other conclusions) with Rudolf Bultmann (1950) and C. H. Dodd (1953) in seeing the result of a group process involving multiple sources, multiple redactions, or both from a "Johannine school" of Christians.

By the way, since you mentioned C.H. Dodd, I thought I’d also mention that, although Dodd doesn’t hold to the traditional authorship of John, he wrote of the external evidence for the traditional authorship of John...

“Of any external evidence to the contrary that could be called cogent I am not aware.” -Historical Tradition in the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963), p. 12

There seems to be some circularity in this statement if it is meant there is something intellectually dishonest about arguing for the traditional authorship of all the NT books. So I’m not really sure what your point is here even if it were accurate (it isn’t, but I will get to that). And I don’t see how holding to inerrancy is relevant to authorship of the Gospel of John (or the other Gospels for that matter). I don’t hold to inerrancy myself but I’m familiar enough with the doctrine to know the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy says nothing explicitly about affirming the traditional authorship of the Gospels. The closest it seems to come is to deny attempts to undermine texts in the Bible when that text claims authorship (e.g. Pauline epistles, etc).After the middle of the twentieth century, all commentators that I found arguing for the Apostle John as author (Craig Blomberg, Andreas Köstenberger, Charles Quarles, Craig Keener) are sectarian inerrantists that also argue that all of the traditional ascriptions for the other NT books are correct.

”Article XVIII: We deny the legitimacy of any treatment of the text or quest for sources lying behind it that leads to relativizing, de-historicising, or discounting its teaching, or rejecting its claims to authorship.”

Since the Gospels do not explicitly claim authorship a signer of the statement can argue for non-traditional authorship of the Gospels without violating the statement. In other words, those who hold to the statement are not necessarily arguing for traditional authorship because they are doctrinally obligated to do so.

At any rate, your assertions about scholarship are not entirely accurate. For example, Craig Bloomberg does not hold to Pauline authorship of Hebrews despite it being traditionally attributed to Paul. Likewise, neither does Andreas Köstenberger. Similarly, Craig Keener says he doesn’t know who wrote Hebrews either and offers several possibilities.

Although you don’t mention them in your (very small) sampling of conservative scholars Carson and Moo also, after reviewing the arguments, maintain a similar open ended view of the authorship of the Gospel of Matthew, Hebrews, and 2 Peter. William Lane Craig, although he thinks questions about Gospel authorship are interesting, doesn’t think answering such questions are crucial to their historical reliability. Ben Witherington III, who has signed inerrancy statements (although he says he prefers the term “truthful and trustworthy”), has suggested the Gospel of John may have been written by Lazarus. Mike Licona, after having lost his position at Liberty University because of criticisms of his views (Licona was accused of denying inerrancy and admitting contradictions by Norman Geisler), was hired and defended by Houston Baptist University. Licona argues there is a decent case for the traditional authorship of the Gospels. Daniel B. Wallace argues for the plausibility of the traditional authorship of the Gospels (and other NT books) rather than those attributions necessarily being “correct” as you put it. And I think Wallace’s approach is fairly indicative of the scholarship holding to the traditional authorship.

The bottom line is there are a number of good scholars on both sides of the fence, some of whom hold to the traditional authorship of John and some of whom do not. So an appeal to authority isn’t going to settle the question, I’m afraid. Now, I’m happy to concede that many scholars, perhaps the majority of all scholars, do not hold to the traditional authorship of John (or any of the Gospels). If that is your argument, I concede the point. Aside from the point itself, I’m not really sure what your point is or how it proves your claim.

I'm breaking this into two posts because I don't see how the above either addresses the evidence directly or proves your claim.

Things atheists say:

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

- Goose

- Guru

- Posts: 1707

- Joined: Wed Oct 02, 2013 6:49 pm

- Location: The Great White North

- Has thanked: 79 times

- Been thanked: 68 times

Re: The Gospel Writers

Post #68Part 2.

That said, there are a number of lines of evidence that, although they fall short of proof, are consistent with traditional authorship.

I will let Daniel B. Wallace summarize Wescott’s “Concentric Proofs”

Irenaeus tells us he had knowledge of the works of Papias and that Papias had heard John and was a companion of Polycarp.

Irenaeuas also tells us he had heard Polycarp who had spoken to witnesses of Jesus.

Euesebius records a letter written to Florinus from Irenaeuas which tells that Polycarp had spoken to John (and others who had seen Jesus).

So, Irenaeus implies direct personal contact with Polycarp and knowledge of Papias' writings. Two different sources that each had direct personal contact with John.

As far as historical methodologies go, Irenaeus alone is sufficient to establish authorship even if only by virtue of his temporal proximity to John never mind that he says he knew Polycarp who knew John, he knew Papias’ writings, and that Papias knew John. To put Irenaeus’ attribution to John in historical perspective consider two other works from antiquity which are, strictly speaking, just as anonymous as the gospels yet traditional attribution of authorship is generally accepted. Caesar’s Gallic War Commentaries and Tacitus’ Histories.

Similar to what we have with Papias there are a few brief mentions of Caesar’s “memoirs” from contemporary writers like Cicero but nothing that explicitly links these memoirs to our Gallic War Commentaries. And some reasons to think these memoirs were not our Gallic War Commentaries. At least 120 years later Plutarch attributes the Commentaries to Caesar in his biography of Caesar in Parallel Lives. But the first explicit external attribution of authorship of the Gallic War Commentaries to Caesar comes from Suetonius writing about 160 years later in his Life of Caesar.

Likewise Pliny speaks of Tacitus writing a history but nothing explicitly linking those writings to our Histories. With some reasons to think Pliny wasn’t referring to our Histories. The first writer to explicitly attribute authorship of our Histories to Tacitus is Tertullian writing about 100 years later. Tertullian never mentions his source and may have been going off Pliny’s ambiguous letters. Unlike the line from Ireneaus reaching back to John we don’t even have that much for Tacitus’ Histories.

In other words, the external evidence for the authorship of these two secular works (and many others) is no stronger than external evidence for John (and the Gospels). Therefore, whatever we say about the strength of the external evidence for the Gospels we must also say about the strength of the external evidence for these two secular works. Whatever we conclude about the authorship of the Gospels because of the weakness of the external evidence for the Gospel of John (and the other Gospels) we must likewise conclude about these secular works. Are you prepared to conclude Caesar’s Gallic War Commentary and Tacitus’ Histories were probably not authored by the respective traditional authors? You had better be because that is what your reasoning implies if we apply it those secular works.

As for the external evidence you’ve mentioned Irenaeus. I’m not sure why you would then say “[t]hat’s it.”

Here’s a summary of the external evidence for John up to around the beginning of the third century which limits sources to no more than about 150 years after composition.

1. Evidence from Justin Martyr (c. 150 - 160 AD):

Although Martyr does not explicitly attribute the fourth Gospel to John (Martyr doesn’t explicitly attribute the other three Gospels to any particular author either but rather refers to the “memoirs of the apostles” as he makes use of them) he is familiar with the unique doctrines found in the Gospel of John, quotes from it as scripture, and does link it to apostolic authorship along with the other Gospels. Also Martyr does seem to be aware of the tradition that the book of Revelations was attributed to John and that some Gospels were drawn up by disciples and some were drawn up by followers of the disciples. It seems inexplicable that Justin would be familiar with the unique doctrines found in the Gospel of John, quote from it as authoritative scripture, be aware of the obscure traditions that this prophecy was attributed to John, and be aware that some Gospels were authored by disciples and some by those who followed them but somehow not be aware of the more prominent tradition that the fourth Gospel was attributed to John.

2. Evidence from the Anti-Marcionite Prologues (c. 160 - 180 AD):

Some scholars have dated these prologues to around 160 - 180 AD. The prologue to John is particularly of interest as it appeals to the authority of Papias’ writings. In other words, in his writings Papias had claimed John wrote a Gospel. That gives a contemporary source to John, through Papias, attesting to John having authored a Gospel.

3. Evidence from the Muratorian fragment (c. 170 - 180 AD):

4. Evidence from Theophilus of Antioch (lived c. (?) - 183 AD):

5. Evidence from the Ptolemæus (c. 170 AD?) as recorded by Irenaeus:

Irenaeus’ polemic against the Valentinians has inadvertently provided a source from outside the orthodox church who attributed the words in the fourth Gospel to John, the disciple of the Lord.

6. Evidence from Heracleon (c. 175 AD?) as recorded by Origen in his commentary on John:

Again, as with Ptolemæus, Heracleon is another non-orthodox source who attributes the words of the fourth Gospel to John, the disciple.

7. Evidence from Irenaeus (lived c. 130 - 202 AD, wrote c. 180 AD):

8. Evidence from Clement of Alexandria (lived c. 150 - 215 AD, wrote c. 195 AD):

9. Evidence from Tertullian (c. 200 AD):

10. Evidence from Origen (lived c. 184 - 253 AD, wrote c. 230 AD):

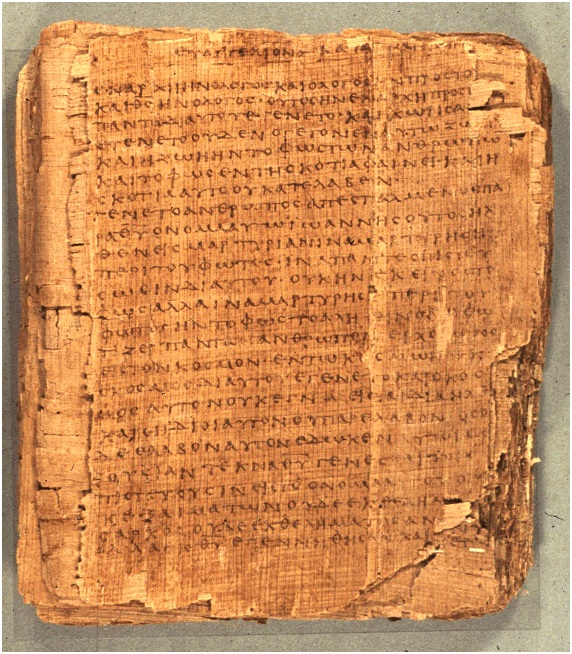

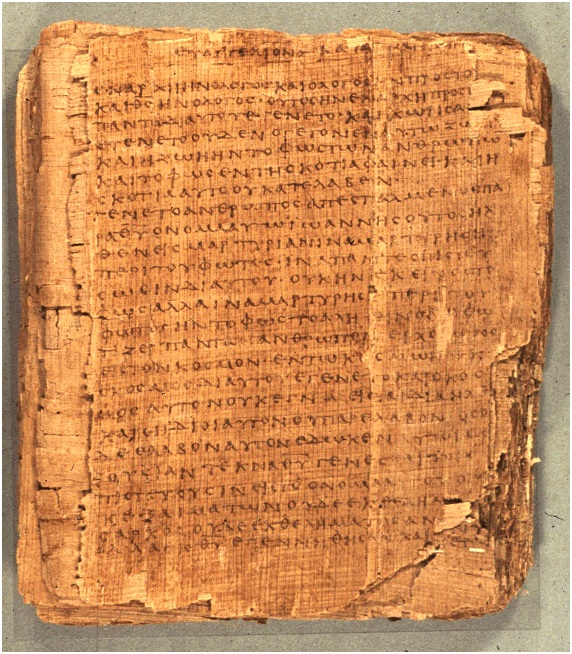

11. Papyrus 66 (c. 200 AD)

Although it’s difficult to see p66 has the title “Gospel according to John.”

12. Papyrus 75 (c. 175 – 225 AD)

If, in the early church, there was no expectation or method to accurately maintain authorial traditions that went back to the authors themselves then the alternate case must be something along the lines that authorial attributions were arbitrarily added at some unknown point by unknown people who did not have knowledge of who wrote the respective Gospel. Someone simply decided to assign the fourth Gospel to John, presumably, to bolster its credibility. Each source above, then, received their respective authorial tradition which was not grounded in historical knowledge but grounded in the desire to bolster the credibility of the fourth Gospel. But if this were the case then we would expect there to be numerous competing traditions since any witness to the life of Jesus would bolster credibility. We would expect to see the fourth Gospel assigned to another disciple or someone like Lazarus for example (either in the manuscript tradition or patristic writings) if it was the practice to arbitrarily assign names which would bolster credibility. But we don’t see that.

If we think of each of the twelve sources listed above as an opportunity in its own right to either attribute authorship to the fourth Gospel or to have received a tradition attributing it to John and endorsed that attribution then we have (at least) 12 opportunities for an attribution of authorship to exist. Although each source may have had knowledge of a prior John tradition there’s no reason to think any particular source must follow the prior tradition handed down to them since the traditions were not expected to be grounded in historical knowledge but were rather grounded in the desire to bolster the credibility of the work. Each source above, then, as well as any unknown preceding source had numerous eyewitness choices that they could have assigned to the fourth Gospel. To name a few there were, of course, any one of the 12 disciples. Additionally, depending upon how loosely each source might have understood “disciple” and interpreted John 21:24, there were many more possible choices. For instance Lazarus or one of his sisters Mary or Martha, or Mary mother of Jesus, or Mary Magdalene, or Mary the wife of Clopas, or James the brother of the Lord, or Nicodemus, or Joseph of Arimathea to name few. In fact, Acts 1:15 estimates there were about 120 brethren within roughly 40 days of Jesus’ death. That implies 120 people that could have been a witness to the life of Christ and thus compose the total set of possible outcomes.

But let’s keep it to just the 12 disciples for the sake of argument since they might represent the obvious pool of possibilities. The chance, then, that all 12 sources listed above would just happen to either choose John or have received that tradition given 12 possible choices is 1/12^12 or 1/8,916,100,448,256 or a probability of 1.21 x 10^-13. Now, that’s a non-zero probability but it’s so low that we can say it’s impossible.

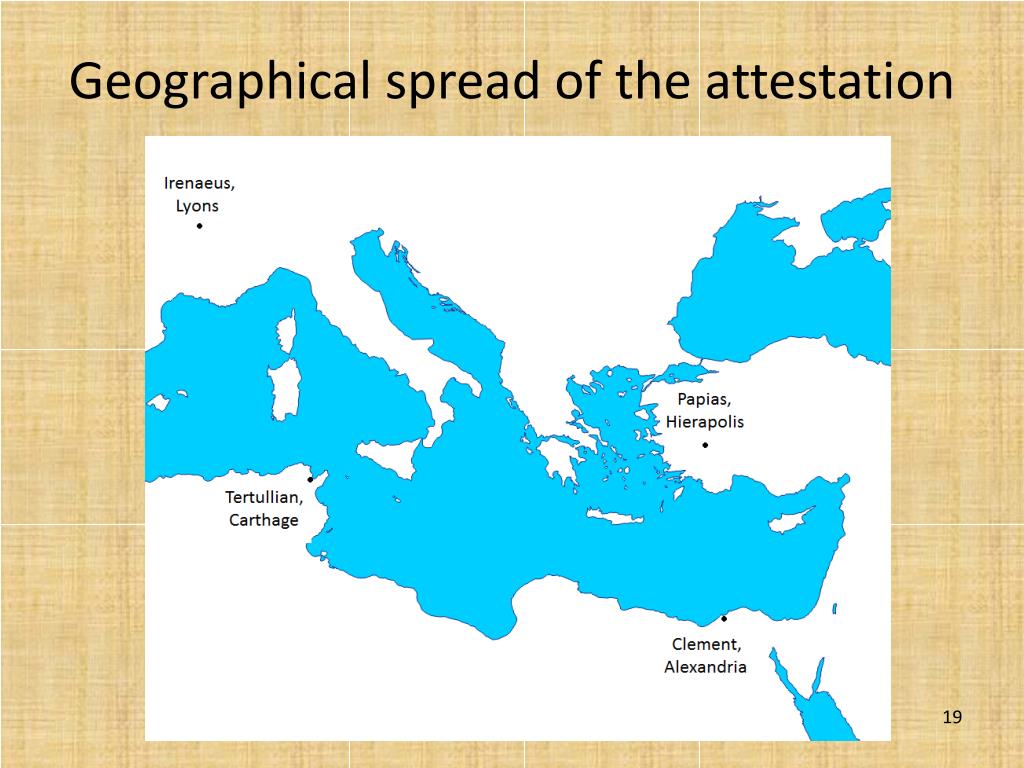

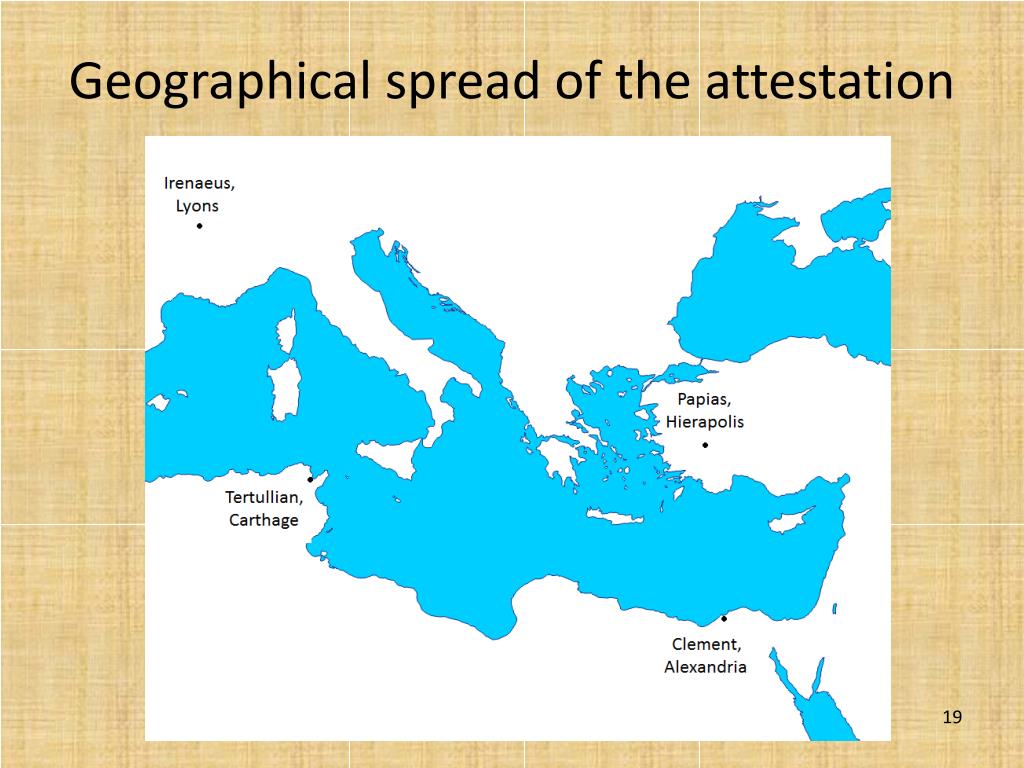

Now consider the following image provided by Timothy McGrew in a slide in his presentation that neatly illustrated the geographical separation of some of these writers some of whom were (in the case of Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Clement) writing around the same time.

I’m not a big fan of applying Bayes Theorem to historical questions but let’s take a page out of Richard Carrier’s book for the sake of interest since you seem to want to argue from probabilities.

What is the posterior probability, then, that John authored the fourth Gospel given the evidence of multiple sources saying he did?

1. Let P(A)= John authored the fourth Gospel. There are varying estimates but I will be conservative and assume a literacy rate of 2% in the first century making this our prior probability that John wrote a Gospel.

2. Let P(B)= attributions of the fourth Gospel to John.

3. Let P(B|A)= 30% probability we have the evidence we do given that it’s true John authored the fourth Gospel. This is difficult to determine statistically and I admit it’s somewhat subjective so I am being conservative here and assuming only 30% of the Christian texts that we might expect to mention John’s authorship of the fourth Gospel do mention it.

4. Let P(B|~A)= 1/12^3 or 5.787037 x 10^-4 or 0.0005787037. The probability we would have three sources attributing the fourth Gospel to John given that John did not author it. To be conservative I’ve assumed only 3 sources above either received the John tradition or chose John themselves rather than all 12.

5. Let P(~A)= 98% or .98 (1- P(A))

Thus we have a 91% posterior probability that John wrote the fourth Gospel given the external evidence.

(I’ve trimmed out the rest of your post because I saw nothing salient there that argues against John being the author of the fourth Gospel. If you think I’ve overlooked an important argument let me know and I will double back on it.)

The internal evidence for John, like most ancient biographies, makes no explicit internal claim to authorship. As such we look to the internal evidence to be either consistent or inconsistent with external attributions. That’s typically all that can be said for internal evidence of texts which do not explicitly claim authorship in the text itself.Difflugia wrote: ↑Sun Sep 20, 2020 6:21 pmThe evidence for the argument that John of Zebedee wrote the Gospel of John can be summed up with the following:That's it. As to the first point, the Gospel never explicitly includes, even obliquely, the name of the "Beloved Disciple" (unless it means Lazarus) and 21:24 is ambiguous as to whether the "Beloved Disciple" is even intended as the author.

- The "Beloved Disciple" mentioned in the Gospel and taken to be its author might mean John of Zebedee.

- Irenaeus (Against Heresies, 3.1.2) claimed that the Fourth Gospel was written by "John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia."

That said, there are a number of lines of evidence that, although they fall short of proof, are consistent with traditional authorship.

I will let Daniel B. Wallace summarize Wescott’s “Concentric Proofs”

There are more internal lines of evidence consistent with John’s authorship but that’s enough for now.Daniel B. Wallace wrote:A. CONCENTRIC PROOFS

(1) The Author was a Jew

He quotes occasionally from the Hebrew text (cf. 12:40; 13:18; 19:37); he was acquainted with the Jewish feasts such as the Passover (2:13; [5:1]; 6:4; 11:55), Tabernacles (7:37), and Dedication/Hanukkah (10:22); he was acquainted with Jewish customs such as the arranging of water pots (ch. 2) and burial customs (11:38-44).

(2) The Author was a Jew in Palestine

He knows that Jacob’s well is deep (4:11); he states that there is a descent from Canaan to Capernaum; and he distinguishes between Bethany and Bethany beyond the Jordan; in short, he is intimately acquainted with Palestinian topography.8

(2) The Author was an Eyewitness of What he Wrote

He stated that he had beheld Christ’s glory (1:14) using a verb (θεάομαι) which in NT Greek always bears the meaning of at least physical examination (cf. BAGD); there are incidental comments about his being there (Judas slipped out at night [13:16] 4:6 [the sixth hour], etc.).

(4) The Author was an Apostle

He has an intimate knowledge of what happened among the disciples—cf. 2:11; 4:27; 6:19, etc.

(5) The Author was the Apostle John

He is exact in mentioning names of characters in the book. If he is so careful, why does he omit the name of John unless he is John? Further, his mention of John the Baptist merely as “John” (1:6) implies that if he is to show up in the narrative another name must be given him—such as “the beloved disciple”—or else confusion would result.

I don’t see why he needs to when Irenaeus establishes a direct line right back to John. Besides, that’s not much of an argument since we have to take the word of many ancient writers in regards to attributing authorship (and other matters).As to the second, Irenaeus doesn't mention the source of his information, so we have to take his word for it.

Irenaeus tells us he had knowledge of the works of Papias and that Papias had heard John and was a companion of Polycarp.

“And these things are borne witness to in writing by Papias, the hearer of John, and a companion of Polycarp, in his fourth book; for there were five books compiled by him.” - Irenaeus Against Heresies 5.33.4

Irenaeuas also tells us he had heard Polycarp who had spoken to witnesses of Jesus.

”But Polycarp also was not only instructed by apostles, and conversed with many who had seen Christ, but was also, by apostles in Asia, appointed bishop of the Church in Smyrna, whom I also saw in my early youth, for he tarried [on earth] a very long time, and, when a very old man, gloriously and most nobly suffering martyrdom, departed this life, having always taught the things which he had learned from the apostles, and which the Church has handed down, and which alone are true.” - Against Heresies 3.3.4

Euesebius records a letter written to Florinus from Irenaeuas which tells that Polycarp had spoken to John (and others who had seen Jesus).

”For when I was a boy, I saw you in lower Asia with Polycarp, moving in splendor in the royal court, and endeavoring to gain his approbation. I remember the events of that time more clearly than those of recent years. For what boys learn, growing with their mind, becomes joined with it; so that I am able to describe the very place in which the blessed Polycarp sat as he discoursed, and his goings out and his comings in, and the manner of his life, and his physical appearance, and his discourses to the people, and the accounts which he gave of his intercourse with John and with the others who had seen the Lord. And as he remembered their words, and what he heard from them concerning the Lord, and concerning his miracles and his teaching, having received them from eyewitnesses of the 'Word of life,' related all things in harmony with the Scriptures.” – Irenaeus, as recorded by Eusebius, Church History 5.20.5-6

So, Irenaeus implies direct personal contact with Polycarp and knowledge of Papias' writings. Two different sources that each had direct personal contact with John.

John -> Polycarp -> Irenaeus

John -> Papias -> Irenaeus

John -> Papias -> Irenaeus

As far as historical methodologies go, Irenaeus alone is sufficient to establish authorship even if only by virtue of his temporal proximity to John never mind that he says he knew Polycarp who knew John, he knew Papias’ writings, and that Papias knew John. To put Irenaeus’ attribution to John in historical perspective consider two other works from antiquity which are, strictly speaking, just as anonymous as the gospels yet traditional attribution of authorship is generally accepted. Caesar’s Gallic War Commentaries and Tacitus’ Histories.

Similar to what we have with Papias there are a few brief mentions of Caesar’s “memoirs” from contemporary writers like Cicero but nothing that explicitly links these memoirs to our Gallic War Commentaries. And some reasons to think these memoirs were not our Gallic War Commentaries. At least 120 years later Plutarch attributes the Commentaries to Caesar in his biography of Caesar in Parallel Lives. But the first explicit external attribution of authorship of the Gallic War Commentaries to Caesar comes from Suetonius writing about 160 years later in his Life of Caesar.

Likewise Pliny speaks of Tacitus writing a history but nothing explicitly linking those writings to our Histories. With some reasons to think Pliny wasn’t referring to our Histories. The first writer to explicitly attribute authorship of our Histories to Tacitus is Tertullian writing about 100 years later. Tertullian never mentions his source and may have been going off Pliny’s ambiguous letters. Unlike the line from Ireneaus reaching back to John we don’t even have that much for Tacitus’ Histories.

In other words, the external evidence for the authorship of these two secular works (and many others) is no stronger than external evidence for John (and the Gospels). Therefore, whatever we say about the strength of the external evidence for the Gospels we must also say about the strength of the external evidence for these two secular works. Whatever we conclude about the authorship of the Gospels because of the weakness of the external evidence for the Gospel of John (and the other Gospels) we must likewise conclude about these secular works. Are you prepared to conclude Caesar’s Gallic War Commentary and Tacitus’ Histories were probably not authored by the respective traditional authors? You had better be because that is what your reasoning implies if we apply it those secular works.

As for the external evidence you’ve mentioned Irenaeus. I’m not sure why you would then say “[t]hat’s it.”

Here’s a summary of the external evidence for John up to around the beginning of the third century which limits sources to no more than about 150 years after composition.

1. Evidence from Justin Martyr (c. 150 - 160 AD):

”For Christ also said, Unless you be born again, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.”Now, that it is impossible for those who have once been born to enter into their mothers' wombs, is manifest to all... And for this [rite] we have learned from the apostles this reason. Since at our birth we were born without our own knowledge or choice, by our parents coming together, and were brought up in bad habits and wicked training; in order that we may not remain the children of necessity and of ignorance, but may become the children of choice and knowledge, and may obtain in the water the remission of sins formerly committed, there is pronounced over him who chooses to be born again, and has repented of his sins, the name of God the Father and Lord of the universe; he who leads to the laver the person that is to be washed calling him by this name alone. - 1 Apology 61

”For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them; that Jesus took bread, and when He had given thanks, said, This do in remembrance of Me, this is My body; and that, after the same manner, having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, This is My blood; and gave it to them alone. Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn.” – 1 Apology 66

”And further, there was a certain man with us, whose name was John, one of the apostles of Christ, who prophesied, by a revelation that was made to him, that those who believed in our Christ would dwell a thousand years in Jerusalem; and that thereafter the general, and, in short, the eternal resurrection and judgment of all men would likewise take place.” - Dialogue with Trypho 81

”For in the memoirs which I say were drawn up by His apostles and those who followed them”- Dialogue with Trypho 103

”For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them; that Jesus took bread, and when He had given thanks, said, This do in remembrance of Me, this is My body; and that, after the same manner, having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, This is My blood; and gave it to them alone. Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn.” – 1 Apology 66

”And further, there was a certain man with us, whose name was John, one of the apostles of Christ, who prophesied, by a revelation that was made to him, that those who believed in our Christ would dwell a thousand years in Jerusalem; and that thereafter the general, and, in short, the eternal resurrection and judgment of all men would likewise take place.” - Dialogue with Trypho 81

”For in the memoirs which I say were drawn up by His apostles and those who followed them”- Dialogue with Trypho 103

Although Martyr does not explicitly attribute the fourth Gospel to John (Martyr doesn’t explicitly attribute the other three Gospels to any particular author either but rather refers to the “memoirs of the apostles” as he makes use of them) he is familiar with the unique doctrines found in the Gospel of John, quotes from it as scripture, and does link it to apostolic authorship along with the other Gospels. Also Martyr does seem to be aware of the tradition that the book of Revelations was attributed to John and that some Gospels were drawn up by disciples and some were drawn up by followers of the disciples. It seems inexplicable that Justin would be familiar with the unique doctrines found in the Gospel of John, quote from it as authoritative scripture, be aware of the obscure traditions that this prophecy was attributed to John, and be aware that some Gospels were authored by disciples and some by those who followed them but somehow not be aware of the more prominent tradition that the fourth Gospel was attributed to John.

2. Evidence from the Anti-Marcionite Prologues (c. 160 - 180 AD):

”The Gospel of John was revealed and given to the churches by John while still in the body, just as Papias of Hieropolis, the close disciple of John, related in the exoterics, that is, in the last five books.”

Some scholars have dated these prologues to around 160 - 180 AD. The prologue to John is particularly of interest as it appeals to the authority of Papias’ writings. In other words, in his writings Papias had claimed John wrote a Gospel. That gives a contemporary source to John, through Papias, attesting to John having authored a Gospel.

3. Evidence from the Muratorian fragment (c. 170 - 180 AD):

”The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke. Luke, the well-known physician, after the ascension of Christ, when Paul had taken with him as one zealous for the law, composed it in his own name, according to [the general] belief. Yet he himself had not seen the Lord in the flesh; and therefore, as he was able to ascertain events, so indeed he begins to tell the story from the birth of John. The fourth of the Gospels is that of John, [one] of the disciples. To his fellow disciples and bishops, who had been urging him [to write], he said, 'Fast with me from today to three days, and what will be revealed to each one let us tell it to one another.' In the same night it was revealed to Andrew, [one] of the apostles, that John should write down all things in his own name while all of them should review it... For 'most excellent Theophilus' Luke compiled the individual events that took place in his presence as he plainly shows by omitting the martyrdom of Peter as well as the departure of Paul from the city [of Rome] when he journeyed to Spain...”

4. Evidence from Theophilus of Antioch (lived c. (?) - 183 AD):

”And hence the holy writings teach us, and all the spirit-bearing [inspired] men, one of whom, John, says, ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God,’ showing that at first God was alone, and the Word in Him. Then he says, ‘The Word was God; all things came into existence through Him; and apart from Him not one thing came into existence.’” - To Autolycus 2.22

5. Evidence from the Ptolemæus (c. 170 AD?) as recorded by Irenaeus:

”Further, [the Valentinians] teach that John, the disciple of the Lord, indicated the first Ogdoad, expressing themselves in these words: John, the disciple of the Lord, wishing to set forth the origin of all things, so as to explain how the Father produced the whole, lays down a certain principle,—that, namely, which was first-begotten by God, which Being he has termed both the only-begotten Son and God, in whom the Father, after a seminal manner, brought forth all things. By him the Word was produced, and in him the whole substance of the Æons, to which the Word himself afterwards imparted form...Thus, then, does he [according to them] distinctly set forth the first Tetrad, when he speaks of the Father, and Charis, and Monogenes, and Aletheia. In this way, too, does John tell of the first Ogdoad, and that which is the mother of all the Æons. For he mentions the Father, and Charis, and Monogenes, and Aletheia, and Logos, and Zoe, and Anthropos, and Ecclesia. Such are the views of Ptolemæus.” – Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1.8.5

Irenaeus’ polemic against the Valentinians has inadvertently provided a source from outside the orthodox church who attributed the words in the fourth Gospel to John, the disciple of the Lord.

6. Evidence from Heracleon (c. 175 AD?) as recorded by Origen in his commentary on John:

”Heracleon supposes the words, ‘No one has seen God at any time,’ [John:18] etc., to have been spoken, not by the Baptist, but by the disciple.” – Origen, Commentary on John 4.2

Again, as with Ptolemæus, Heracleon is another non-orthodox source who attributes the words of the fourth Gospel to John, the disciple.

7. Evidence from Irenaeus (lived c. 130 - 202 AD, wrote c. 180 AD):

”Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia.” - Against Heresies 3.1.1, c. 180AD.

8. Evidence from Clement of Alexandria (lived c. 150 - 215 AD, wrote c. 195 AD):

”Again, in the same books, Clement gives the tradition of the earliest presbyters, as to the order of the Gospels, in the following manner: The Gospels containing the genealogies, he says, were written first. The Gospel according to Mark had this occasion. As Peter had preached the Word publicly at Rome, and declared the Gospel by the Spirit, many who were present requested that Mark, who had followed him for a long time and remembered his sayings, should write them out. And having composed the Gospel he gave it to those who had requested it. When Peter learned of this, he neither directly forbade nor encouraged it. But, last of all, John, perceiving that the external facts had been made plain in the Gospel, being urged by his friends, and inspired by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel. This is the account of Clement.” - as recorded by Eusebius CH 6.14.5-7

9. Evidence from Tertullian (c. 200 AD):

”We lay it down as our first position, that the evangelical Testament has apostles for its authors...Of the apostles, therefore, John and Matthew first instil faith into us; while of apostolic men, Luke and Mark renew it afterwards.” - Against Marcion 4.2

"The same authority of the apostolic churches will afford evidence to the other Gospels also, which we possess equally through their means, and according to their usage. I mean the Gospels of John and Matthew while that which Mark published may be affirmed to be Peter's whose interpreter Mark was. For even Luke's form of the Gospel men usually ascribe to Paul. And it may well seem that the works which disciples publish belong to their masters. Well, then, Marcion ought to be called to a strict account concerning these (other Gospels) also, for having omitted them, and insisted in preference on Luke; as if they, too, had not had free course in the churches, as well as Luke's Gospel, from the beginning." - Against Marcion 4.5

"The same authority of the apostolic churches will afford evidence to the other Gospels also, which we possess equally through their means, and according to their usage. I mean the Gospels of John and Matthew while that which Mark published may be affirmed to be Peter's whose interpreter Mark was. For even Luke's form of the Gospel men usually ascribe to Paul. And it may well seem that the works which disciples publish belong to their masters. Well, then, Marcion ought to be called to a strict account concerning these (other Gospels) also, for having omitted them, and insisted in preference on Luke; as if they, too, had not had free course in the churches, as well as Luke's Gospel, from the beginning." - Against Marcion 4.5

10. Evidence from Origen (lived c. 184 - 253 AD, wrote c. 230 AD):

”Among the four Gospels, which are the only indisputable ones in the Church of God under heaven, I have learned by tradition that the first was written by Matthew, who was once a publican, but afterwards an apostle of Jesus Christ, and it was prepared for the converts from Judaism, and published in the Hebrew language. The second is by Mark, who composed it according to the instructions of Peter, who in his Catholic epistle acknowledges him as a son, saying, 'The church that is at Babylon elected together with you, salutes you, and so does Marcus, my son.' And the third by Luke, the Gospel commended by Paul, and composed for Gentile converts. Last of all that by John.” - as recorded by Eusebius CH 6.25.4-7

11. Papyrus 66 (c. 200 AD)

Although it’s difficult to see p66 has the title “Gospel according to John.”

12. Papyrus 75 (c. 175 – 225 AD)

If, in the early church, there was no expectation or method to accurately maintain authorial traditions that went back to the authors themselves then the alternate case must be something along the lines that authorial attributions were arbitrarily added at some unknown point by unknown people who did not have knowledge of who wrote the respective Gospel. Someone simply decided to assign the fourth Gospel to John, presumably, to bolster its credibility. Each source above, then, received their respective authorial tradition which was not grounded in historical knowledge but grounded in the desire to bolster the credibility of the fourth Gospel. But if this were the case then we would expect there to be numerous competing traditions since any witness to the life of Jesus would bolster credibility. We would expect to see the fourth Gospel assigned to another disciple or someone like Lazarus for example (either in the manuscript tradition or patristic writings) if it was the practice to arbitrarily assign names which would bolster credibility. But we don’t see that.

If we think of each of the twelve sources listed above as an opportunity in its own right to either attribute authorship to the fourth Gospel or to have received a tradition attributing it to John and endorsed that attribution then we have (at least) 12 opportunities for an attribution of authorship to exist. Although each source may have had knowledge of a prior John tradition there’s no reason to think any particular source must follow the prior tradition handed down to them since the traditions were not expected to be grounded in historical knowledge but were rather grounded in the desire to bolster the credibility of the work. Each source above, then, as well as any unknown preceding source had numerous eyewitness choices that they could have assigned to the fourth Gospel. To name a few there were, of course, any one of the 12 disciples. Additionally, depending upon how loosely each source might have understood “disciple” and interpreted John 21:24, there were many more possible choices. For instance Lazarus or one of his sisters Mary or Martha, or Mary mother of Jesus, or Mary Magdalene, or Mary the wife of Clopas, or James the brother of the Lord, or Nicodemus, or Joseph of Arimathea to name few. In fact, Acts 1:15 estimates there were about 120 brethren within roughly 40 days of Jesus’ death. That implies 120 people that could have been a witness to the life of Christ and thus compose the total set of possible outcomes.

But let’s keep it to just the 12 disciples for the sake of argument since they might represent the obvious pool of possibilities. The chance, then, that all 12 sources listed above would just happen to either choose John or have received that tradition given 12 possible choices is 1/12^12 or 1/8,916,100,448,256 or a probability of 1.21 x 10^-13. Now, that’s a non-zero probability but it’s so low that we can say it’s impossible.

Now consider the following image provided by Timothy McGrew in a slide in his presentation that neatly illustrated the geographical separation of some of these writers some of whom were (in the case of Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Clement) writing around the same time.

I’m not a big fan of applying Bayes Theorem to historical questions but let’s take a page out of Richard Carrier’s book for the sake of interest since you seem to want to argue from probabilities.

What is the posterior probability, then, that John authored the fourth Gospel given the evidence of multiple sources saying he did?

1. Let P(A)= John authored the fourth Gospel. There are varying estimates but I will be conservative and assume a literacy rate of 2% in the first century making this our prior probability that John wrote a Gospel.

2. Let P(B)= attributions of the fourth Gospel to John.

3. Let P(B|A)= 30% probability we have the evidence we do given that it’s true John authored the fourth Gospel. This is difficult to determine statistically and I admit it’s somewhat subjective so I am being conservative here and assuming only 30% of the Christian texts that we might expect to mention John’s authorship of the fourth Gospel do mention it.

4. Let P(B|~A)= 1/12^3 or 5.787037 x 10^-4 or 0.0005787037. The probability we would have three sources attributing the fourth Gospel to John given that John did not author it. To be conservative I’ve assumed only 3 sources above either received the John tradition or chose John themselves rather than all 12.

5. Let P(~A)= 98% or .98 (1- P(A))

P(A|B) = P(B|A) x P(A) / P(B|A) x P(A) + P(B|~A) x P(~A)

.3 x .02 / .3 x .02 + .0005787037 x .98 = .006 / .006 + .0005671296 = .006 / .0065671296 = .9136 or 91.36%

.3 x .02 / .3 x .02 + .0005787037 x .98 = .006 / .006 + .0005671296 = .006 / .0065671296 = .9136 or 91.36%

Thus we have a 91% posterior probability that John wrote the fourth Gospel given the external evidence.

(I’ve trimmed out the rest of your post because I saw nothing salient there that argues against John being the author of the fourth Gospel. If you think I’ve overlooked an important argument let me know and I will double back on it.)

I don’t see why that’s particularly odd or an argument against any of the original disciples being the author. Josephus refers to “the Jews” over fifty times in the first chapter alone of his Wars of the Jews. Besides when John refers to “the Jews” in context to Jesus’ opponents he seems to be referring to the Jewish religious leaders.Aside from the possible claim of the "Beloved Disciple" as the author, most other details of the Gospel argue against any of the original disciples being an author. It seems odd that the son of a Galilean fisherman in the first century would refer to the opponents of Jesus as "the Jews."

I don’t see how that's unlikely given the existence of the Septuagint and authors like Josephus recording (in Greek) conversations between Jews. Some writings of which might likewise be considered Josephus' own memoirs as well.John's Jesus is fond of ironic word play, some of which only works in Greek ("born again" vs. "born from above," for example). That would mean that the Galilean John of Zebedee is either remembering conversations with Jesus, his fellow Galilean, in Greek or incorporating later traditions into what is nominally a memoir, neither of which seems particularly likely.

Things atheists say:

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak

"For the record...I think the Gospels are intentional fiction and Jesus wasn't a real guy." – Difflugia

"Julius Caesar and Jesus both didn't exist." - brunumb

"...most atheists have no arguments or evidence to disprove God." – unknown soldier (a.k.a. the banned member Jagella)

"Is it the case [that torturing and killing babies for fun is immoral]? Prove it." - Bust Nak